Microtek Interview PCB007-May2019

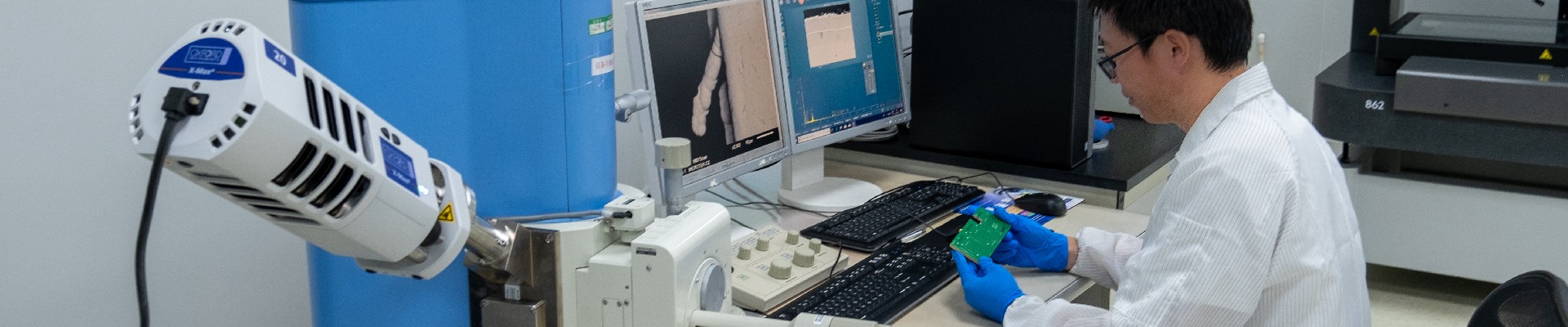

2019.05.21Microtek Labs: It has been over 15 years since Bob Neves started Microtek Laboratories China to service the local Chinese market. On a recent visit to Microtek’s Changzhou facility, Barry Matties, publisher, and Edy Yu from the I-Connect007 China team spoke with Bob, who serves as the chairman and CTO. Bob discusses the changes he has seen living and doing business in China over the past 15 years, most notably the in- creased importance of standards and testing as China moves into manufacturing more high- reliability products. Barry Matties: First, we’re here at your facility in Changzhou, and Microtek Labs has been at this facility for 12 years. Can you talk a little about Microtek? Bob Neves: Microtek is a laboratory that |

spe-cializes in testing for the supply end of the electronics industry. The primary companies that we do testing for are PCB manufacturers. We do testing and validation for the suppli- ers to the PCB industry, and people that buy PCBs and use them in assembly. The top end of our testing services for our customer base usually starts at the solder joint, and we do |

Bob Neves at Microtek’s Changzhou facility. evaluations from the solder joint all the way through the raw materials, such as glass, ep- oxy, copper, and all of the other things that go into making a PCB. We become involved in the relationship between the supplier and cus- tomers as an

| independent source to determine whether the product does or doesn’t meet the requirements. Sometimes, it’s just routine, and we check on ongoing things, but other times, when there’s an issue, a problem, or a discrep- ancy, we mediate. We test to IPC standards primarily, but we also test to local GB standards. We test to IEC standards and a variety of customer internal standards, the biggest of those being from the transportation industry right now. Transpor- tation is the fastest growing segment of the market because it’s also the fastest changing. People in the transportation segment have to |

design and integrate things into their vehicles that they never have had to do before, so there are lots of new designs, chips, and compo- nents going into their electronics. And the ex- pectation is that these electronics are going to last a very long time. Right now, most of the commercial market has been geared toward the things that don’t last a long time, such as cellphones and cameras where if they fail, it’s not as critical, unlike if something in a vehicle would fail, life is at risk. Overall, there’s a lot of effort around auto-motive as well as the transportation market in general, which is where we see our biggest growth. China is opening up its internal air- plane market and creating their own airplanes for both commercial and cargo use and trying

Overall, there’s a lot of effort around automotive as well as the transportation market in general, which is where we see our biggest growth.

| to export those. The same thing is happen- ing with trains and subways. China has train cars and subways in 100 countries around the world, and they have several active builds of trains around the world right now and are bid- ding for a bunch of others. China is looking to be an international supplier of public transport and a leading supplier of electric buses and ve- hicles in general around the world. Matties: Is there also a space race going on in China? Neves: It’s interesting. The government side of the electronics industry is a totally closed mar- ket, and they have their own supply chains. China is doing something similar to what the U.S. used to be back in the old days when military contractors like Rockwell, Honeywell,

|

Lockheed Martin, etc., would have the entire supply chain as their own. We don’t see any- thing coming from the space, aerospace, and military sides of the market; that’s entirely their own industry. People attend trade shows seminars from those segments, but not as of- ten. They don’t participate in the commercial side of things as much. Matties: You’ve been living in China for many years now. Neves: I’ve been living there full-time for about 15 years, but I started coming in the early ‘90s almost every year, so it has been interesting watching the differences between China from then to now. Matties: You mentioned automotive, and look- ing at the sheer number of cars on the road compared to just eight or nine years ago is quite incredible. Neves: Yes. I gave a paper on that at IPC APEX EXPO 2019 with a whole bunch of numbers as far as the number of cars that are being sold in China and that | are on the road. It dwarfs any- thing that’s happening anywhere else in the world. China struggles to keep up with the in- frastructure. Being a foreigner, you have to go through registration, insurance, and all of the things you take for granted. I’ve watched that whole process become a lot more streamlined and successful. China monitors emission to make sure that cars are not spewing too much junk into the air, and the Chinese people want to get ahead with good quality of life. Over- all, China has gone through many progressions and stages lately. Matties: How has that changed in the type of testing or work that’s coming through your facility? Neves: If I go back to the early days, the one thing that we brought to the market from our U.S. business was integrity—people relied on us to always give them an unbiased opinion of what we were testing. In the early market, China was |

Lockheed Martin, etc., would have the entire supply chain as their own. We don’t see any- thing coming from the space, aerospace, and military sides of the market; that’s entirely their own industry. People attend trade shows seminars from those segments, but not as of- ten. They don’t participate in the commercial side of things as much. Matties: You’ve been living in China for many years now. Neves: I’ve been living there full-time for about 15 years, but I started coming in the early ‘90s almost every year, so it has been interesting watching the differences between China from then to now. Matties: You mentioned automotive, and look- ing at the sheer number of cars on the road compared to just eight or nine years ago is quite incredible. Neves: Yes. I gave a paper on that at IPC APEX EXPO 2019 with a whole bunch of numbers as far as the number of cars that are being sold in China and that are on the road. It dwarfs any- thing that’s happening anywhere else in the world. China struggles to keep up with the in- frastructure. Being a foreigner, you have to go through registration, insurance, and all of the things you take for granted. I’ve watched that whole process become a lot more streamlined and successful. China so focused on getting ahead and qualifying for things that testing and certificates were merely a barrier to registering or shipping your product. Chinese customers didn’t see it as a necessary part of the whole process. A lot of things hap- pened where the expectation of our customers was that we would let them pass regardless of actual results, but we wouldn’t do that. The first five years of our business was very challenging because we had a reputation for not being flex- ible in our testing methodologies. | As China became more interested in the transportation industry and other industries that require high reliability, companies became aware of this and were very concerned. Cus- tomers started looking for someone that they could count on to give them unbiased opinions, which is when the market really changed for us because we had developed a reputation for in- tegrity. It almost killed us in the first few years, but now it has made us a leader in this particu- lar market in China because all of the custom- ers that utilize our testing services know that they’re getting unbiased data from us. Matties: It’s data they can trust. Neves: Absolutely. Our testing is a fraction of the price of the value of whatever we’re test- ing. For a $100–300 test, customers might be making decisions that affect millions of dol- lars of product, so what the test costs is rath- er meaningless; our customers aren’t as con- cerned with that. They want to make sure that they’re making the right de- cision on their two to five million dol- lars’ worth of product. We’ve managed to keep that value proposition, which has caused us to be successful in a market where the price is everything. Usually, cost is one of the first three questions customers ask. But we’ve been able to maintain our price lev- els to sustain growth and all the other things we do here without the pressure that some competitors have to cut cor- ners on what they supply the custom- er. We sell with integrity, and people

|

Matties: And for a lot of dealings in China, that’s starting to matter more and more on a lot of different levels. You mentioned earlier that you’re dealing with suppliers to the fab- ricators. Is this primarily around the base ma- terials? Neves: Our main tier with the relationships be- tween the board fabricators is base materials, solder mask, and copper suppliers—the prima- ry supply base for materials. We also work for them and their suppliers. Copper-clad manu- facturers receive copper foil, resin, and glass. We verify the capabilities and properties of those materials whether it’s organic, inorganic, or metallic because they have become complex in the last 20 years. We used to have a hand- ful of supply materials, but now we have hun- dreds of options. | Matties: Materials are a big opportunity and problem all at the same time because there are so many to choose from, as you mentioned. Who’s driving the change in the board shops to use new materials? Neves: The real change was to lead-free mate- rials. Lead-free drove the materials from what they were to what they are today. The problem was that the increase in temperature that lead- free provided does a lot of damage to organic materials, and the solution wasn’t simple. As you increase heat resistance and change your want that, so they buy from us. The flame lab.

|

Thermal shock (RTC) lab 2. organic formula to do that, the material be- comes untenable for other properties. Materi- als become more brittle, more prone to frac- ture and increases in the coefficient of thermal expansion, and have more problems with ad- hering to the glass. It creates a bunch of prob- lems that people have worked to fix for ap- proximately 15 years. Resin systems now are very complex and usually make up three, four, or sometimes even five different resin systems, fillers and additives that prevent fracturing, and bonding promoters, UV blockers, etc. Peo- ple don’t realize how complex the makeup of these materials is. As you add complexity to a batch process, there are more opportunities for things to go wrong. That’s where a lot of the materials have changed over the years. You also have a change in operating frequency. There are lots of changes happening in RF and autonomous driving that require lidar or radar, which are all

| happening in the high GHz range. Typical or- ganic materials don’t do well in that area; they tend to absorb the radiation, which isn’t good. These devices are very low radiation, and if your material is absorbing all of the radiation, it doesn’t get to your chips. Companies have had to change materials to adjust to that, or they’ve had to use different combinations of these materials or multilayers that might have a layer of material specifically for high fre- quency. Other materials deal with lead-free, expan-sion, and holding holes together, so you have all these weird composites. The advent of rigid- flex has become more mainstream because an average vehicle has kilometers of wiring in it. All of that cable adds weight and cost; there’s a big interest now in reducing that with flexible cables. The flex industry has also made bigger movements from a standpoint of where they were percentage wise to where they are today. Matties: When you look at the different mar- kets here, aside from automotive, where do you see the larger areas of growth? Neves: In addition to automotive, which is an established industry that’s growing rapidly with a lot of R&D and engineers and a mar- ket that everybody is chasing, there’s also the whole 5G market and everything that will eventually connect to 5G, including IoT. There are things that you never thought would be connected to the internet. Now, there’s an ex- pectation of having 30–40 devices connecting to your home network. Buying a router and plugging it in is not a good solution anymore because that might not connect to a camera in the far corner of the house or the doorbell, thermostat, or oven that wants to tell your smartphone or watch that your turkey is done. All of these things now have to be integrated, and some companies that need to do this are not used to dealing with electronics at all. Some are used to making mechanical parts, but now they have to bolt on electronics that talk to the internet or an internal router or server through a combination of sensors, CPUs, RF, and soft- ware. Many companies are trying to figure out |

Humidity lab 2. how to do this economically. Another layer of OEMs, the Foxconns and Flextronics of the IoT market, are working their way through the sys- tem right now and offering these services to companies. They’re going to be the suppliers of the bolt-on electronics, and as these com- panies grow, they’re going to bring it in-house. Matties: When you travel through China, it’s clear that they’ve embraced technology in a big way on a lot of different fronts. I can go to a local fruit stand and they won’t even accept cash, for example; everything is e-pay now. Traffic signals and cameras everywhere, so there are a lot of electronics. What has it been like for you to watch this transformation from a technology point of view? | Neves: It’s quite challenging because the rate of change is unlike anything I’ve ever experi- enced before. The interesting thing is watching how the locals accept it. The average Chinese person has become accustomed to this pace of change, and it’s just normal to them. They ex- pect that when they leave and go on vacation for a couple of weeks, they’re going to come back to something different, such as a new road, building, or technology. China is used to change, but not everyone in the world is. I can go to places in the U.S. or Europe that haven’t changed in 15–20 years.

|

Meanwhile, none of what we passed driving from the train sta- tion to our office existed when I first arrived 15 years ago; it was just farmland. Where this building now sits used to be in the middle of nowhere. But now there’s solid development the entire way to the city center. The Chinese are used to it and don’t spend a lot of time planning details ahead of time be- cause plans change so rapidly, and otherwise, nothing would ever get done. If they need fiber optic ca- bles, they dig up a road and put some in. If they need a road or a drain system, they put one in, etc. They plow ahead, and if they make a mistake, they fix it and move on. Matties: Back to the testing, when should peo- ple consider a testing service? Neves: If I look at the documents and IPC test methods out there that talk about test- ing, they’re very basic guides; they only tell you generally how to accomplish a test. For instance, there is a long learning curve associ- ated with doing a humidity test. You can’t just buy a humidity chamber and a meter and start testing. There’s a huge amount of | understand-ing you have to gain about your water system, environment, cleanliness, the wires you use, the techniques to put the samples in the cham- ber, and how to put the meter together. Dozens of little things aren’t a part of what’s published out there, and that knowledge only comes from having experience. Microtek started in ‘86. We’ve been doing testing in this market for a very long time, so we have a lot of learned knowledge. It has been passed on and acquired from doing what a lot of competitors don’t have. Other compa- nies say, “Let’s get into the automotive mar- ket. We’ll buy some chambers and meters, and we’ll be an automotive test laboratory right now,” but they haven’t spent 30 years doing testing in the automotive market. For example, we started with Delphi and Sun Microsystems

|

eons ago back when they were the early lead- ers in reliability and technology of PCBs. We gained a lot of experience from the au- tomotive and the U.S. aerospace market with satellites—things that people rely upon. We tested the boards on the Spirit and Opportu- nity Mars Rovers that lasted 6 and 15 years re- spectively after they were expected to die. And that’s what customers want to find; problems cause their company pain, money, time, and time to market, so it’s not about a few dollars in testing. Maybe the purchasing agents com- pare, but the engineers certainly don’t. The en- gineers want to have good data so they can fulfill their responsibilities. We’ve been doing this for so long that we know about everything that could affect your test results. Matties: Pain and the associated problems are big motivators for testing, but do people look at it as an opportunity? Do they say, “We want to expand into a new market, and we need to prove a process,” for example. Neves: Not really. We do some testing asso- ciated with material changes and things that they can’t do internally. If they want to im- prove a process, it’s usually a material change, so they’ll send us something, and we’ll de- termine if | the material is better or worse. But again, that’s usually driven from higher up in the supply chain. Somebody at the OEM level says, “I would like to make a change to this material and want to verify how you’re able to manufacture it.” Matties: Do you ever deal with the circuit board designers? Neves: They never go to the test side of it. They read and learn by trial and error. Matties: Is there an opportunity to gain knowl- edge to help improve circuit design? Neves: The material suppliers have seen that their materials get specified in at the design phase. They’ve developed an entire sales focus based on informing the designers of the bless-ings of using their materials and how they can solve the design problems that they’re facing with their materials. There’s a lot of informa- tion focused on the material supplier to the OEMs and the designers within those OEMs. But most of the supply chain doesn’t care all that much. They’ve all just said, “We’ll do what you want us to do. If it works, great, but if it doesn’t, we can build it again.” The bigger PCB shops have teams that review designs and will work with the designers, saying, “We’ve seen this before, and this isn’t going to work. You should probably redesign this.” |

There is communication between the board shop and the design team supplying the prod- uct. That has been a sales point for smaller and larger OEMs. The smaller ones that are do- ing design work don’t expect to get the pro- duction order—their job is to work with the design team. And the large OEMs can’t afford a $50 million mistake. Their customer would not be happy with them and would ask why they didn’t catch it before it happened. Edy Yu: You said China is focusing on all types of transportation. What standards are you test- ing for transportation or aerospace? Neves: One of the things we’ve seen with the China market is that there’s a push by the government to use GB standards. | But just like the IEC standards, GB standards—like all interna- tional standards—tend to lag behind the mar- ket a little bit. IPC has really pushed the effort to try and meet the needs of the transportation market. For example, China Rail Group and Comac have worked with IPC and their efforts

Reflow simulation lab.

|

in the transportation business to upgrade IPC standards. Now, you’re seeing automotive and transportation addendums, such as IPC-6012, which is a board standard, as well as IPC-A-610 and J-STD-001, which are assembly standards. Now, we have input from all other markets as well. They’re all part of IPC’s Task Groups Asia, which is working on adapting these stan- dards to meet these requirements. The domes- tic high-reliability market has realized that IPC standards are at the forefront of this. Eventu- ally, the GB standards will catch up. Histori- cally, IEC and GB standards have taken a lot of technology from what’s been developed by IPC groups and adopted it to their standards. Rather than waiting, they’ve chosen to be pro- active, adopt it now, and then work internally in the GB system to move that into their inter- nal documents. And we’re happy to do that. We want to get as much input from as many different industries as we can.

We want to get as much input from as many different industries as we can.

| Yu: That’s interesting the Chinese train com- pany wants to work with IPC. Neves: They do. GB standards are domestically developed. Our technical team has worked on some GB committees as well because the prob- lem with international standards is that they have to be translated into Chinese. If you adopt an English standard, then you have to trans- late it. Each industry has its own language, per se, because since Chinese is an old language, it doesn’t have a lot of relevant technical terms in it, so it’s hard to find the right translator to translate the English technical standards into Chinese standards. And that’s where IPC’s Task Groups Asia has come in. They’ve taken tech- nical experts from the Chinese industry and put them in at the ground floor of the documents. Instead of having a translation after the fact,

|

Yu: Back in 2003, you had just moved to serve the local market. When you look back, was this the plan all along? Neves: When I looked at the China market and decided to open a business here, unlike most people who wanted to take advantage of the low cost and exporting things out of China, I came in to service the domestic market. Five years ago, 98% of our business was just China, and that was on purpose. Because of our exper- tise in the Asia market, we’ve seen an influx of business coming to us externally. That prob- ably makes up 8–9% of our business coming in from outside of China because we’ve estab- lished ourselves as a | world leader. We receive stuff from Europe and other places as well for some of the specialty things that we do better than anyone else in the world. But the goal has always been to service the local market locally because you can’t service the Chinese market from outside of China; it’s almost impossible. The one thing I’ve learned from all of my years since coming here in the ‘80s is that China is a very unique place. Ev- erything runs a little bit differently, so unless you’re fully here and integrated, you cannot run a successful business from outside. And the market caught up with us. When we first arrived, we were a service business. Nobody understood, and they would ask us what we made. When I’d say, “We don’t make any- thing,” they didn’t understand our service- |

based business. Now, they’re beginning to understand. China is starting to shift toward a more service-based model, whether that’s from an app or a software standpoint to spe- cialty businesses like Microtek that provides high-end services. The big companies are still going to do ev- erything themselves, such as Huawei, ZTE, and Haier. Those companies have decided that if they need to do something, they will build a division. They don’t want to subcon- tract anything. And every place that has under- gone development goes through that process where they bring it all in, and then at some point, they spin it all off. But that hasn’t hap- pened yet here. That’s another development in the future that will help us grow—when larger companies start realizing that their laboratory and testing services are all cost centers. They don’t make them any money; they’re just full on cost. And they have significant burden of overhead that we can save them. Microtek can save them money because we spread our bur- den of overhead over a bunch of companies while they’re stuck with it just for themselves. Matties: But in many cases, everything in Chi- na is a secret. There’s still some of that mental- ity out there. | Neves: A lot of the innovation comes from look- ing at what’s in the industry and doing it better ourselves—not necessarily spending a lot of time doing the innovation themselves directly, but innovating on how to make it better, faster, and cheaper. And that’s always been China’s success. And another thing that’s changing is the people, education, and engineering here is leading to a lot of new and unique stuff. Matties: Maybe less copycat stuff? Neves: I don't know if copycat is the right word. It’s looking at a product and saying, “Wow, that’s expensive. I can do that cheaper.” Matties: Well, there was a foundation of copy- catting, which is part of the ongoing nego- tiations between China and the IP. With that aside, I understand that you’re saying they’ve reached a level of innovation where they’re in- novating on their own. |

Neves: Correct. But every market economy has gone through this. When the new Americans left Europe to come to America, they carried a lot of innovation with them. When Japan was rebuilding after the war, they gained a mar- ket as the cheap electronics copy place and evolved into what they are today. It’s happen- ing in a similar way in China. Matties: When you look at China 15–20 years ago, there weren’t the manufacturing process- es and knowledge that there are today. Back then, they were learning through partnering with US OEMs. Now, they’re capable of manu- facturing and competing on a world-class lev- el with their own product lines because they have the experience. Neves: When you look at the local experts who have been doing it for 5–6 years, they’re good, but in the West, we wouldn’t consider people “experts” unless they’ve been doing it for 20+ years, and nobody has that here. However, if a particular field has only been open for 10 years and someone has 10 years of experience, then I’d consider them an expert. | Humidity lab 1.

|

Future humidity lab 3. Matties: And the shift in manufacturing to smart factories and the reduction of operators by law in some regions is playing a big role in China on the economic makeup. b style="font-weight:bold;">Neves: Automation is a natural progression of the increase in the cost of labor that China has been undergoing. For our first 10 years in busi- ness, our cost of labor at the lab increased 15% year on year; now, we’re down to 6–8%. It’s leveled off, but it’s still significant. If I look at the cost of doing business today versus when I started, it’s well over double. | Matties: But I would think that the jobs you offer at Microtek are more desirable than the traditional manufacturing jobs. Neves: I would like to think so because I value people and the training that I put into employ- ees. Some companies say, “We don’t want peo- ple to stay more than a year because we don’t want to have to pay them more money. We’ll piece our jobs so they’re easy to train and I can cycle people in and out.” Microtek doesn’t do that. I can’t hire a kid out of college who will have the knowledge that’s gained from running all of the tests that we do because there’s just no school for that. We have a training program here and levels of operators and educational

|

courses that we run so that they can earn their way through our system. As they gain more knowledge, they gain more benefits and we provide more incentives to keep them growing and learning more. Our turnover rate here is very low. Matties: It's a specialty job. Neves: Right, and we’re very careful who we hire. We want to hire people that intend to stay for a long time. Matties: A career path rather than a stepping stone. Neves: Absolutely. Matties: How many employees do you have? Neves: We just passed 50 people at the end of last year, so we’ve hit that level where ev- ery company has to create mid-management positions. We’ve had to restructure things these past few quarters to go to the next level. Growth has been very consistent for us due to all of these changes in transportation and IoT, and those market segments are also expecting huge growth. | Matties: You keyed in on it earlier. Your success is really tied to the rate of change that happens here serving a domestic market. And it looks like the change is happening at an accelerated pace on a daily basis. Neves: You can't sustain 15% year on year forever because it’s an exponential curve. At some point, to keep a steady rate of growth, you have to reduce your annual percentage, and China is seeing that now. How is that go- ing to work instead of the expectation of a 6% growth, which would be fantastic anywhere in the world, when people are looking at it, say- ing “Meh?” Matties: It barely keeps us moving. But it looks like 5G is going to be a big factor in this for the coming years. |

咨询专员

咨询专员